McGill seals research bonds with India

McGill seals research bonds with India McGill University

User Tools (skip):

McGill seals research bonds with India

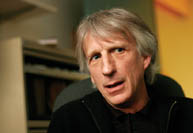

Vice-Principal Research and International Relations Denis Thérien

Owen Egan

Fifteen or 20 years ago, a university mission to forge ties with India would probably have been viewed through the prism of foreign aid and technology transfer. Once again, the advanced, technological West would be coming to the rescue of the needy developing world.

What a difference a couple of decades can make. In late November, 18 McGill University researchers, led by Denis Thérien, vice-principal research and international relations, visited India as part of the McGill Scientific Mission 2006. Their goal was to pave the way for future scientific partnerships with leading universities and institutions in such cities as Delhi and Bangalore, with the emphasis on the word "partnerships." Though massive social problems and inequalities still exist, since India began to liberalize its economy in the early 1990s, has surged ahead to become a major global economic, technological and scientific player. A receiver of foreign aid in the 1970s and 80s, India now builds its own fighter jets, maps the human genome and talks about sending manned missions to the moon within ten years.

"We visited the top institutions of India, like the National Centre for Biological Sciences, the Indian Institute of Science and the Raman Research Institute in Bangalore," said Thérien. "These places are on a completely equal footing with a university like McGill. The infrastructure, the colleagues that you meet, it's absolutely the same."

The India mission was spurred by a convergence of factors, Thérien said. When he arrived to take on the role of VP Research in late 2005, Canada and India had just signed a science and technology agreement, and McGill was invited to join a mission to India led by Quebec Premier Jean Charest. At the same time, the university was taking a long, hard look at the way it had managed international collaborations in the past.

"Traditionally, Researcher X was doing his business over here, and Researcher Y was doing his collaboration over there — completely unaware that X had something going on," Thérien said. "Now we will require much more strategic concentration on a few areas that are central to McGill's strategic plan, because we need to make optimal use of scarce resources."

To that end, Thérien was accompanied by researchers in fields where McGill has world-class core competencies relevant to India, including nanoscience, neuroscience, AIDS, public policy, astrophysics and agriculture, among others. They were greeted with open arms by their Indian colleagues, said Thérien, who seemed particularly gratified that McGill followed up on contacts made during the earlier visit with Premier Charest.

McGill's high profile in India also helped. The university has more than 600 alumni in India, among them the daughter and son-in-law of Manmohan Singh, India's prime minister, both of whom earned their doctorates at McGill.

McGill plans to invest in funding the start-up of several research partnerships. "We are taking a person-to-person approach that will help advantageously position not only our researchers but also our research groups, when the time comes to attract major outside funding sources," said Thérien.

The McGill Scientific Mission coincided with one organized by Raymond Bachand, Quebec's minister of economic development, innovation and export trade. That delegation also included McGill Engineering Professor Mourad El-Gamal and Management Professor Vihang Errunza.