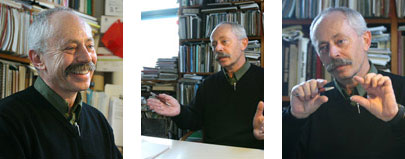

David Covo on being part of one of the few schools that still teach freehand drawing classes to architectural students: "The process of drawing — at its most basic — is how we always have, and how we always will, express architectural ideas. Words help, but the image is indelible."

Owen Egan

ENTRE NOUS

with David Covo, director of the School of Architecture

Shortcut leads to long haul

In 1968, an engineering freshman named David Covo had what he now calls a "serendipitous collision" with architecture that changed the path of his professional life forever. Switching majors, the Montreal native earned a BArch in 1974, returned to McGill in 1977 as a part-time professor and was named Director of the School of Architecture in 1996. Now in the final few months of his mandate at the helm of the school, Covo sat down with the McGill Reporter and reflected on the school's storied past while casting a philosophical eye on the future.

Tell us about how you became interested in architecture.

I enrolled in engineering at McGill in 1967 and my plan was to get into aeronautical engineering. Halfway through my second semester, I took a shortcut to avoid a press of people in the McConnell lobby and found myself cutting through a public review of senior or upper-year student design work in the School of Architecture; I was immediately hooked. The next day I spoke to the person responsible for admissions to architecture who, as it turned out, was Derek Drummond, and I applied to transfer. I took a shortcut and never left.

What is the role of the architect in society?

The role of the architect is in a state of constant evolution. One of the differences today is the importance attached to environmental responsibility. Like many other professional programs, we've taken steps to make sure that concepts of sustainability and sustainable design are significant elements of our core programs. Every one of our students goes through an exercise sensitizing them to the environmental responsibility of the architect in relation to the process of designing a building. They have to be confident that they can design and build a building without reducing, as has been done in the past, the value of other related systems.

How does this definition drive the School of Architecture?

It puts pressure on us to develop our teaching and research links with our colleagues in engineering and beyond. For example, it gives us the opportunity to work closely with new partners in Mechanical Engineering or in Mining, Metals and Materials. These types of opportunities not only become irresistible, but also strategic in the near future. We're also putting together a new joint program in urban design which has just been approved by the University. A new option in our Masters programs, it is a collaboration between Architecture and Urban Planning. In September, each of us will be offering an option in urban design at the Masters level. In the longer-term, we're also working with the Université de Montréal (U de M) and their schools of architecture, landscape architecture and urbanism on developing a new joint degree — a Master of Urban Design — that will be bilingual, multicultural and interdisciplinary, and be attractive to professionals from all over the world.

Landscape architecture? The average layperson doesn't often associate landscaping with erecting buildings.

But they should. U de M has one of the few Landscape Architecture programs in the country and we do a joint studio with them at the undergraduate level. It's great to see our students work with someone their own age who says "No you can't put silver maples there, you really should be looking at honey locusts because the canopy is so much more transparent." And the U de M students are amazed when our students suggest that concrete beam might be more effective than steel in a particular situation.

Has your role as director changed since 1996?

Fundraising has become a major preoccupation. I've spent more time fundraising over the past three years than I did in the previous eight. We've been fortunate because we've received some major gifts from supporters like Phyllis Lambert, Gerald Hatch and Gerald Sheff, but we're always looking for new opportunities.

Finally, I understand you're a competitive sailor. Is that your way of relieving stress?

When you're sailing, you're disconnected, literally, from the land. The minute you commit to a crew and a competition, you have to give it everything, 100 percent. It demands that you focus completely, in a way we aren't often required to do.

Architecture is seen as visual but it isn't only visual; it's a very sensual experience. It's the same with sailing. You take information in from a variety of sources. You're listening to the sounds the boat makes and the sound of the wind, and wind shifts can actually smell different. The lines of communication are non-verbal. In the end, when you come ashore there is a sense of rejuvenation that leaves you ready for anything the next day can throw at you.

|

|

|