Norbert Schoenauer: brought humanity to housing

Norbert Schoenauer: brought humanity to housing McGill University

User Tools (skip):

Norbert Schoenauer: brought humanity to housing

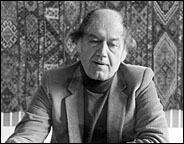

Professor Norbert Schoenauer

Professor Norbert Schoenauer |

|

Earlier this semester I faced a dilemma. I had to prepare the two-hour lecture for the "History of Housing" class in the afternoon, and I also had to get down to finalizing what I would say at a tribute for Norbert Schoenauer, a cherished colleague who died this summer at the age of 78.

While I paced though my yard, I was wondering which event deserved more attention. I thought: this is typically a question that I would have pitched to Norbert. Suddenly I could almost hear his voice from the clouds: "Pieter, prepare your lecture first and if there's time left, write down some notes if you have to. The future is more important than the past."

The reason I almost instinctively thought of asking Norbert was because "ask Norbert" has been a button on the phone of the School of Architecture for 40 years. And the button has been pushed untold many times by thousands of students and dozens of colleagues and friends.

His open, clear mind, his calm demeanour, his non-judgmental attitude earned him a status in the architectural community that rivals the one of Dear Abby in the lovelorn one. And his column was his always open door.

Norbert built buildings, designed cities, was an adviser to governments, wrote influential books and taught generations of architects.

The focal point of his activity was the study and design of housing. For an architect to concentrate on housing as single-mindedly as Norbert did is unusual. The profession has always been ambivalent toward housing, and some practitioners even deny it is legitimate architecture.

His passion for housing was all-encompassing; it went from the humble nomad's hut to opulent mansions.

To Norbert, housing and neighbourhoods were the birthplace and the cradle of social life. His view was that a house, any house, is important not only as an architectural construct but as a social, cultural and economic incubator as well.

I had the good fortune of getting to know Norbert over a period of 30 years. First I was his student. He was a gifted teacher who took the job of interacting with students seriously. He expressed his strong views in a typically gentle manner. If he said, "May I suggest to you" he really meant, "I've thought for 30 years about what I'm going to say, so listen up you!"

He had a strong commitment to architecture in a broad cultural and ethical and common-sense context. For instance, his suggestion that apartments housing families should not be more than six stories high was based on the eminently human fact that a mother can still recognize her child on the street from that height, and on the ecological one that a good tree reaches about that high.

His resistance to cars in the city was based on the idea of fair play: why allow the few to pollute and crowd the many? His opposition to urban sprawl was grounded in his aversion to the enormous waste it entails and the social poverty it produces.

At the end of term the students in his design studio, as well as two or three graduate students, were invited to his lovely row house on Prospect Street. Food and drinks were aplenty and Norbert and his wife Astrid were the consummate host and hostess. The evening ended in what I understood was a typical fashion. Norbert opened the black upright piano, and, encouraged by a few drinks, started to play an impassioned version of a jazzy boogie-woogie.

A few years after I graduated, Norbert became my employer for a short while, and I was impressed that even as a lowly teaching assistant he encouraged me to take my involvement with McGill seriously. As I remember it, he told me, "You have your finger on the pulse, let me know what you think, anytime you wish."

After being appointed to a full time position I became his colleague. We had a chance to travel on a few occasions, and I was impressed by his endless curiosity and by his stamina. He out-walked many students and myself in places as varied as Chicago, Budapest, Prague and Karlsbad, loving every minute of it and engaging all and sundry in debates about architecture, history and politics. And if that ran out there was always gossip, for which he had a great talent.

About three years ago, Norbert asked me if I was interested in teaching the "History of Housing" course. I was taken aback. I knew that this course and the book that he had written as the text for it were the two things most dear to him at McGill. I asked: why do you want to give it up? He said nobody lives forever, and if you want to do it I'll be happy to give you a hand for awhile. I was very touched by this offer.

Giving the course I could pick and choose from the thousands of illustrations that he so laboriously collected over the last four decades. He also said that I could use the textbook History of Housing any way I saw fit. At exactly that time he received the offer of Norton Publishers to publish a new, expanded version of the book. In terms of timing, this offer could not have been better. He threw all his energy into the task of making this third expanded version as perfect as he possibly could. And Maureen Anderson, who has edited almost every word Norbert has written, quite happily made her crucial contribution once more. When I saw Maureen take notes at Norbert's hospital bed for the forthcoming publication by Norton of Cities Suburbs Dwellings, I was very happy to know that Norbert was assured that these two books would continue to disseminate his ideas for many years to come.

Professor of Architecture