The quiet voice of Daya Varma

A quiet man in a brown suit, Daya Varma appears almost exactly as one would expect a respected academic to look. Hard to imagine that if it were not for a scheduling conflict in April involving a conference on health care in India, Varma would have been marching amid the tear gas and water cannons of Quebec City.

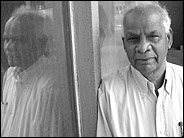

Professor Daya Varma

Professor Daya VarmaPHOTO: Claudio Calligaris |

|

A pharmacology and therapeutics professor who has been at McGill since 1959, Varma has a longstanding interest in many of the issues that raise the ire of anti-globalization protesters.

He is a founding member of CERAS (Centre d'Étude et Ressources d'Asie Sud) and sits on the board of directors of Alternatives, a progressive think tank. He travels frequently to India and Pakistan to speak on development, peace and democracy issues. Closer to home, he recently spoke about the dangers of nuclear arms developments in South Asia at a McGill Student Pugwash conference on the causes of war.

He is also exceedingly modest. "I'm not very interesting, I don't know if you will have anything to write about," he said when first contacted for this story.

Varma's activism is largely related to the South Asian world, especially India and Pakistan. Though there are many causes he champions in that part of the world, he is especially concerned about the recent rise of religious intolerance in India. With the rise to power of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a Hindu fundamentalist party, Varma is troubled by what he sees as the progressive Hinduization of India.

"I come from a tradition of India as a multicultural and multilingual country," says Varma. "When you take a religious or racial view it becomes jingoistic."

That jingoism has revived the flames of religious conflict and the settling of old grievances in India, which has led to violence.

Also, since the election of the BJP minority government, India has engaged in increasing military confrontation with Pakistan, with both powers testing nuclear weapons in recent years. In a press release three years ago for a protest march against the nuclear tests, Varma wrote, "Both Pakistan and India are poor countries and it is deplorable that the governments have given priority to defence and nuclear weapons rather than the well-being of its vast majority."

The mission of CERAS is to promote a secular, multicultural identity both within India and amongst the diaspora in North America. Youth of Indian descent in Canada and the U.S. are particularly vulnerable to a concept of Indian identity that is overly based on religion, rather than on citizenship, in Varma's view.

"In youth there is always a question of identity one way or another; often religious identity is the identity. We don't want youth to become part of these backward religious ideas," he says of the rise of Hindu fundamentalism.

CERAS promotes South Asian unity; in 1999, for instance, it sponsored a human rights conference targeted at young South Asians with speakers jetting in from India and Pakistan to take part. Another project is the Teesari Duniya (Third World) Theatre group, which presents plays aimed at Indian youth that contain themes relating to identity and culture.

"Darma's knowledge and understanding of the situation in South Asia is the backbone of this organization," says CERAS coordinator and co-founder Feroz Mehdi.

"He is a very down-to-earth, very modest person," continues Mehdi. "It was only a couple of years after I knew him that I found out he was a professor at McGill. Whenever we have posters to be distributed he'll say, 'I'll go do it,' or whatever leg-work is required. Of course, the writing part he does best."

The "writing part" includes frequent contributions to the CERAS newsletter, at least one of which, the issue on globalization and India's poor, was widely quoted in the Indian media.

Though Varma's work at McGill largely focuses on the cardiovascular system, he applies his scientific acumen to issues that affect the developing world.

He points out that pharmaceutical companies generally develop their products for Western consumption. Varma has tested the effects of very common drugs, such as Tylenol and Aspirin, on malnourished populations like those found in South Asia.

"Every drug has two effects: therapeutic and toxic," he says, explaining that at low doses in a healthy person, a drug should not express toxicity. At higher doses it will. The difference is the therapeutic margin.

"Generally, I find that the therapeutic margin is much lower when a person is malnourished," he says.

The most dramatic and tragic project Varma has worked on was in response to the 1984 Bhopal disaster. In what is probably the worst industrial accident ever, a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, released 40 tons of toxic methyl isocyanate (MIC), a compound more poisonous than cyanide, into the surrounding area. Over 2,000 died, and tens of thousands more were injured.

Varma was asked to do a study to measure the effect of MIC exposure on pregnant women, which he did both as a statistical survey there and with animal experiments.

"What we found was a very high pregnancy loss, almost 40 per cent," he says. His study was intended to help the victims in their compensation claims, but was never used because the government of India settled for what Varma feels was a pittance.

Giving in to corporate interests is something Varma sees as only getting worse under globalization. India, with a tradition of economic self-sufficiency, is particularly vulnerable to more freely flowing trade. While the U.S. is able to subsidize its farmers up to $200 a hectare, India can afford less than a dollar a hectare. Allowing cloth imports has disrupted the local economy to the point that there has been a measurable increase in the suicide deaths of struggling weavers.

The Free Trade Area of the Americas negotiations are not so much about improving the economies of the countries involved as they are about isolating alternative models, posits Varma. The FTAA, in Varma's view, is an American ploy designed, in part, to isolate Cuba. That country has managed, according to Varma, to have one of the best medicare systems in the world despite being subjected to a punishing American embargo. It's a system other countries could learn from if they had a chance.

"Proper health care can be provided to a vast population of any country and it has nothing to do with the economy of that country," asserts Varma.

He may be soft-spoken, but Varma's voice will make itself heard as the debate over globalization intensifies in the days to come.