McGill exists in the videoconferencing age and the evidence is all around us.

Being in two places at once

With videoconferencing facilities set up in the teaching hospitals, at the Instructional Communications Centre, in the Redpath Museum and in Macdonald Campus's Raymond Building, a typical day at McGill might involve neurological medical rounds held between five countries; McGill-Queen's University Press meetings involving staff from their offices in both Montreal and Kingston; and exchanges between a psychologist here and colleagues in Newfoundland on helping autistic children.

PHOTO: Owen Egan

PHOTO: Owen Egan |

|

But videoconferencing at McGill also has a far more local use: bridging the teaching gap between McGill's downtown campus and the West Island-based Macdonald Campus.

Five courses using the technology to bridge the distance between McGill's two campuses are taught twice per week each, taking in a total of six professors and approximately 160 students.

The process isn't always perfectly smooth.

On a Monday morning, the technology in the Redpath Museum is acting up. The slides on the PowerPoint presentation are ready to roll and the students out at Mac are now visible.

But, for some reason, biology professor Martin Lechowicz, who's giving the lecture this week from the Redpath Museum, has got a small electronic square on him -- at least that's what the students at Mac see.

Lechowicz isn't going to fuss over a small detail. "Marcia, put it [the camera] back to the class and we'll get started," he says to his wife and co-teacher of this course on "Canadian Flora," plant science professor Marcia Waterway.

"I'm sorry for that technical difficulty. We don't know why I've got a target on me," he says dryly.

The "we" refers to Lechowicz and Wayne Mastromatteo, audiovisual technician from ICC. Mastromatteo is there to make the phoneline connections for the videoconferencing and the computer network connections for NetMeeting, the Microsoft software that permits the sharing of applications between two computers on the same local network.

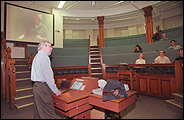

After a 10-minute delay, the lecture is underway. The downtown students have seated themselves directly in front of Lechowicz because he is obliged both to address them and turn his head to the left and address the camera that beams his image out to the videoconference classroom in the Raymond Building. At the same time, he sees the videoconferenced image of the class out at Mac.

Lechowicz must also operate the controls that, today, involve only clicking on the mouse of his laptop in order to advance the slides that have been scanned and ordered in a PowerPoint presentation. What he does here to the computer happens simultaneously to the computer out at Mac, thanks to NetMeeting.

The fact that NetMeeting runs on McGill's own LAN server is key to providing the bandwidth required for good reproduction of the colour graphics used in such courses as "Canadian Flora," explains Carmelo Sgro, assistant producer/director of Multimedia Production and Photography at ICC. "The Internet is far too slow to handle much bandwidth," he says.

Before NetMeeting, which they've only been using since last September, Waterway and Lechowicz would use slides that were sent via the videoconferencing camera through the telephone lines. The quality was poor, however, and every time a slide went up, the remote class would lose the image of the lecturer; the technology couldn't accommodate both images at one time.

To compensate for the slide quality, the couple scanned their slides and put them on a web site so that the students, on their own time, would have a good "textbook" of images for studying. Still, that didn't solve the problem of the missing lecturer.

This past summer, however, Luciano Germani, ICC's man at Mac, Sgro and Telecom worked out the integration of NetMeeting into "Canadian Flora" and both the fuzzy slides and the errant prof were resolved.

The professor appears on a big video screen, while the slides appear on the PowerPoint screen. The slides, scanned and digitized as they have to be for PowerPoint, are equally clear and colourful on both campuses. This day's lecture is on the boreal forest, the forest that dominates Canada's countryside, and there are evergreens galore.

"Juniperus communis is circumboreal," says Lechowicz of the common juniper, explaining that the shrub is found in all boreal forests throughout the world. When a student downtown poses a question, Lechowicz repeats it facing the Mac class on the wall. Then a question from Mac is faintly heard. Again, Lechowicz repeats it, before answering.

It's rare that there's a question from the remote class. Katalin Piller, a U4 student in the McGill School of Environment, finds the process too intimidating. "When you ask a question, you're supposed to press a button so that the camera turns toward you," she explains. "I ask most of my questions in the lab."

Camera-shyness aside, Piller is a fan of this format of course because it allows her to learn from a Mac professor. "For the past four years, I haven't felt I could get to Mac to learn from them. Even with the bus," she points out, "it's still a 45-minute trip."

Videoconferencing at McGill was, in fact, begun to bridge the Mac-downtown divide, which was felt most acutely when, four years ago, the MSE arrived on the scene with a commitment to teaching on both campuses.

"We had a problem and it was the MSE," chuckles John Roston, director of ICC. "It was going to be inefficient to teach the same course on both campuses and [Dean of Science] Alan Shaver supported the creation of a videoconferencing facility."

The original bi-campus courses, now in their third year of videoconferencing, include, from the School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, Peter Jones's "Human Nutrition" and Tim Johns's "Herbs, Foods and Phytochemicals," in addition to "Canadian Flora."

Last year, after much demand from Mac students to have a course on herpetology (reptiles and amphibians), biology professor David Green offered his course in a teleconferenced version. After the initial investment of time -- selecting and having 1,000-plus slides digitized (by the Image Centre of the Department of Biology) -- Green finds the format "as easy as pie."

Green had already converted his "crummy old notes and the use of overheads to using PowerPoint." In fact, he recounts, "using teleconferencing sped up the process. Even though I'd put my notes into PowerPoint, I was still using slides."

For natural resource sciences professor David Bird, however, a debutante both in the process of converting his lectures and teaching tools to PowerPoint and in videoconferencing, the technology isn't yet that simple.

Bird's use of video, illustrations from books, and handouts isn't integrated into PowerPoint, which means using the VCR and documentary camera as well as operating his PowerPoint presentation, on top of remembering to keep himself still, in the camera's eye, so that the downtown students can see him.

And for someone like Bird, director of the Avian Science and Conservation Centre, who is known for his animation and enthusiasm in his lectures on birds, having to keep so much in mind is a bit like clipping his wings -- at least at this stage.

After the retirement of biology professor Bob Lemon, who taught ornithology downtown, Bird was asked to teach his course downtown. Rather than duplicating the course and wasting time in traffic, he decided to use the teleconferencing technology.

"I was quite happy to do it. It's a good technology but frustrating at times."

It's not just the technology that frustrates Bird but the issue of fairness. He worries that the group he sees less, gets less. Last week, for instance, he brought in eggs for the Mac class to examine. While Bird hopes to give a few lectures downtown, and could bring some eggs then, he's not sure when he'll have the extra three hours involved in travel and setting up.

Waterway underscores the point that in converting a course to a video conference/NetMeeting format there is a big investment of time and money.

"Eventually, it will pay off," she says. She warns, however, that in a field like genetics, where the knowledge is rapidly changing, "you'd never recoup the effort" required to keep a digital presentation up to date.

If some of the professors have their quibbles about the technology, the students seem more than satisfied, especially now that they can always have the remote lecturer in view.

They have access to courses they couldn't take before and they all get some personal contact with the professor. Most of the professors give a few lectures in person to the "remote" class and most see all the students in the lab. In Lechowicz and Waterway's course, the entire group of 61 students spend a week together on field excursions before the term begins.

In fact, says Waterway, one of the unexpected benefits of teaching to students on both campuses is the development of "cross-campus" friendships.