PROFILE

Mario Bunge: Philosophy in flux

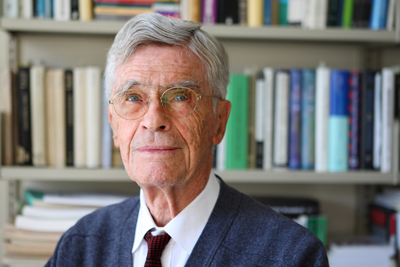

A world-renowned scholar, philosophy professor Mario Bunge has no fewer than 15 honorary doctorates and four honorary professorships.

OWEN EGAN

"I have been reading political news ever since I was seven," says philosophy professor and physicist Mario Bunge. "I learned to read in newspapers, not in school books, which bored me."

In his more than half-century career, Professor Bunge has more than made up for that early aversion to books. Now 88 years old and still teaching in McGill's philosophy department, he has published nearly that many books himself as well as 400 articles. To the book he is currently completing, Political Philosophy, he brings a mix of academic expertise in both philosophy and the philosophy of science, as well personal experience of a political nature. Growing up in Argentina "was a good experience," recounts Bunge. "I was put in jail twice. I didn't have identity papers for 20 years, and could not leave the region. I have never been active in politics, but I have been the target of politics."

Bunge was raised in the intellectually and politically charged world of his parents. His father, a prominent congressman, pioneered legislation in socialized medicine which later influenced the design of Canada's healthcare system. The risks of politics were at times deadly. "My mother made a negative remark about the government while in the market one day. Later, while she was reading the newspaper, a bullet came through the window and narrowly missed her," recalls Bunge. "Nobody has tried to kill me… not that I know of."

Bunge honed his love of philosophy over two decades from books, journals, and fellow amateurs while working towards his doctorate in physico-mathematical sciences, received in 1952. Four years later, he was awarded a chair in philosophy at one university in Buenos Aires and a chair in theoretical physics at another. He arrived at McGill in 1966, was named the Frothingham Professor of Logic and Metaphysics, and currently teaches courses in the philosophy of science, metaphysics and epistemology.

But Bunge has never been content—nor able—to stay within the confines of academia. In 1939, during his studies, he founded a workers' school for 1,000 day labourers to receive practical and popular education, from electrical engineering to the history of the labour movement. The institution was unpopular with the regime in power. "We were harassed by the police until the government shut us down in 1943."

"So, I have been writing this book all my life. It culminates a long career," says Bunge.

Political Philosophy is Bunge's first foray into the field. It assesses political participation and inequality among people and societies, and argues that these two indicators should be incorporated in the UN's Human Development Index, which scores nations according to people's health, education, and income.

Bunge claims there is no shortage of motivations for writing this book. He believes these indicators are in dire condition and desperately understudied. More broadly speaking, he sees political philosophy as stuck in its historical roots. "The mainstream continues to comment on the classics of Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and so forth. I am interested in actual politics, and envisioning possible better societies."

Bunge describes cooperatives, businesses owned and managed by the workers, as one kind of institution that may move the politics in a new direction. Cooperatives succeed on the merit of "direct participation not only in political matters but also economic and cultural matters," explains Bunge. "They are the only businesses in which poor people can participate fully." As for agents that retard progress, Bunge points out that "local domestic politicians who sell out to foreign interests" are numerous and insidious.

Cuba is a prime example, according to Bunge. "People are interested in politics and they have new ideas, but they are starving. There is no political participation. Che Guevara, my fellow countryman and compatriot, said Cubans must grow what they eat. He was rejected because the Soviets offered to buy sugar at a price higher than market value. Today, Cuba produces sugar and imports food from the United States."

Overall, the book is a theoretical work on measuring human development. It proposes conceptual tools that others can wield in empirical research. It incorporates a number of variables that social scientists use but do not explicitly define, such as "inclusion" and "cohesion." "Quantifiable evidence is immensely important," says Bunge. "I am in favour of mathematizing everything you can."

Bunge, who founded the Society for Exact Philosophy in 1976 at McGill, is renowned for promoting more "exact" methods in all modes of research. He sees political science as no exception. "You have much less randomness when you deal with large numbers of people," he says. "It is like dealing with a large number of molecules—there are well-established laws of behaviour."

So how can one individual make a measurable difference? Bunge has much advice to offer. "You can participate in politics minimally by voting, or maximally by joining a non-partisan lobbying organization like Amnesty International. If you can stomach it, join a political party."

If you can't beat them first, of course.