Using computers to test survival success

Using computers to test survival success McGill University

User Tools (skip):

Using computers to test survival success

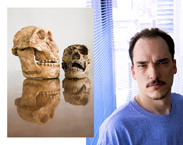

Anthropology professor André Costopoulos

Claudio Calligaris

Although anthropology traditionally relies on human subjects for research, there are now ways to employ computer technology as a substitute for living, breathing beings. Anthropology professor André Costopoulos has found this particularly useful in reconstructing the possible behaviour of hominids from very long ago, by turning to computer modelling to examine the role of memory in human evolution.

Based on archaeological findings, the prevailing theory is that better memory creates a survival advantage. Costopoulos uses the story of two hominid species as an example: "One group, the Australopithecus robustus, is thought to have had less cognitive capacity, and the other, the gracile Australopithecus, had more. With time, the robustus became extinct, while the gracile adapted to their changing environment and survived, thus becoming our ancestor."

Since memory is an important aspect of cognitive capacity, this example appears as a persuasive argument for the role of memory in survival. However, the problem is that this theory has never actually been tested. To relive the past, Costopoulos uses computer modelling, which "provides a way of testing at least some hypotheses about the past and rejecting some of them." His model consists of a computerized landscape that is inhabited by agents who represent people. To test the role of memory, Costopoulos has given his agents different amounts of computer memory, which they use to store information about the location and abundance of subsistence resources that are scattered throughout the landscape. The agents are given the task of collecting and using these resources -- this is what determines their survival success.

At first his findings seemed to confirm the dogma about memory and survival. Agents with less memory became specialists in using only one or two resources, while agents with greater memory relied on a wider array of resources. When supplies were plentiful the group with more memory slightly outperformed the group with less memory. If the environment underwent a sudden dramatic change, be it positive or negative, agents with better memory had the flexibility to adapt to the new situation and switch to exploiting different resources, while those with worse memory did not.

Then Costopoulos created a third scenario, one in which supplies were always scarce. The expectations were that the group with more memory would form strategies for survival and would outperform the group with less memory. Surprisingly, Costopoulos observed the opposite: the low memory group became very good at exploiting the most abundant resource they could find, because they had no recollection of the less significant ones. The better memory group however, became distracted from their search for more plentiful supplies because they also remembered the locations of other resources. In other words, when supplies are scarce, increased memory can sometimes reduce adaptive success.

This finding challenges the existing theory on the relationship between memory and survival. Costopoulos acknowledges that data obtained with his model does not prove that a theory is wrong, but simply adds to our understanding of human behaviour. If this model is accurate, it could answer other key questions about which human characteristics are important for survival, and help secure a place for computer modelling in anthropology.

WARM-SPARK (Writing About Research at McGill-Students Promoting Awareness of Research Knowledge) is a program sponsored by the Faculty of Science, the Offices of the Vice-Principal (Research) and University Relations, NSERC, the Faculty of Engineering and the Faculty of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences. See www.spark.mcgill.ca for more information and articles.