ENTRE NOUS

with Denis Thérien, Vice-Principal, Research and International Relations

The accidental administrator

Denis Thérien on keeping abreast of new technologies: "I am a mathematician, so in my research career I worked primarily with a paper and a pencil. Now, I'm making decisions about things like the genome centre and high-performance computers."

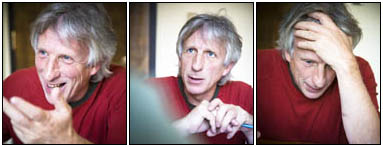

Clad in a red t-shirt and sipping a Coke, Denis Thérien doesn't look like your typical upper administrator. But for the past two years, the affable Thérien has served as McGill's Vice-Principal, Research and International Relations—a key position in an institution that ranks among the world's leading research universities. With a mandate to support McGill's research activities, help guide the research agenda and facilitate the transfer of McGill-developed knowledge and technologies to the commercial market, Thérien's job is, by his own account, "24/7." The former director of the School of Computer Science, Thérien is as confident in his abilities as he is blasé about his sartorial choices ("I don't dress, but I deliver," he laughs). In a brief but animated interview with the McGill Reporter, Thérien spoke about everything from interdisciplinary research to his lifelong love of Tintin comics.

In your two years in office, you have been a vocal advocate of interdisciplinary research at McGill. Why is this so important?

When you are engaged in a purely intellectual enterprise, it is counterproductive to isolate a question from everything that could affect it. If you are truly interested in dealing with real-world questions—which is increasingly the case at universities—you have to explore the questions that exist in the world, not just in your head. The questions faced by society today demand a multi-sided approach.

How is McGill doing on the interdisciplinary side of things?

We have taken some very concrete steps, including launching thematic work groups based on McGill's priorities—such as neurosciences, nanotechnology, environment, computing, health and society, languages and literature. These teams expand research beyond departmental or faculty boundaries by bringing together people from various faculties to meet and discuss how to construct a research agenda or an academic agenda.

Also, just last week we submitted to the research hospital fund of the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the largest grant proposal in McGill history—$100 million in CFI dollars, which means $250 million total. It's gigantic. This project is entirely permeated by interdisciplinarity between clinicians, research doctors, chemists, biologists and so on. Of course, these things take time.

What holds it back?

Although interdisciplinary research is the way the world is going now, we still have administrative structures in place from 100 years ago when interdisciplinarity wasn't even on the table. The challenge is to emphasize interdisciplinary research within these structures.

The easy answer is to say, ‘Why don't you change the structures?' Well, that's easier said than done. It is a constant theme of our reflection—not only here at McGill, but at every institution in the country and in the world. It is clear that no one has found the magic recipe, because once someone finds it, the problem will be solved.

Can you give us an example of existing administrative structures not quite attuned to modern research?

Take funding, for example. SSHRC [Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada] funds the social sciences, NSERC [Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada] deals with science and engineering, and the CIHR [Canadian Institutes of Health Research] funds biomedical initiatives. But what do you do when you have a project that involves all three areas of research? This is a serious issue, because funding affects everything we do. We are working with our colleagues in the federal and provincial governments to try and solve these difficulties, but there are no quick fixes.

On another front, last year you led a McGill delegation to India to pave the way for future scientific partnerships. Where does that stand now?

My office has put together a program to provide co-funding for 14 projects in India. Originally, our call to the McGill community generated somewhere between 30-35 projects that were of an amazing quality. This was the most compelling aspect of this effort—not only did we receive a large quantity of projects, but the quality was extremely high. It was heartbreaking to reject some of these projects. Raymond Bachand, Quebec's minister of economic development, innovation and export trade, was so impressed with our initiative that he went out of his way to provide funding for two more projects so we now actually have 16.

We are also working on a very high-profile biofuel project between people from Mac and colleagues in India, as well as colleagues from the rest of Canada and China and Brazil. In magnitude, this is by far the largest project that we have on the table. Because of its scope, it is a magnificent opportunity to generate international collaboration.

It sounds like this type of partnership will expand to include other countries.

Absolutely. You know, international opportunities have always existed for universities, especially at McGill, where we've built our reputation on the fact that we are extremely international. But traditionally, collaboration was usually done on a researcher-to-researcher basis. Now, it is much more complicated in the sense that, if you want to have real impact, you must have a focused approach. We were successful with India because we organized our community to respond in a really concerted way. Now we are constructing similar models for China and Japan.

It must be very exciting to be on the ground floor of these initiatives.

It is—absolutely fascinating. You read about globalization all the time in the newspaper, but it isn't just an abstract concept; it is really there on the ground. In a place like McGill, we are involved front and centre in the implementation of this concept.

How has globalization changed the dynamics of research universities?

If you look at the research side, you quickly realize that excellence in research necessarily implies internationalization, because, as we were talking about before, partnership is the name of the game. If you want to be right there at the top, you have to collaborate, not only with the best in the city, not only with the best in the country, but with the very best in the world. So you are naturally driven to seek out international opportunities.

And, if you look at international activities, it used to be that the driving force behind international activities was trade. Well, forget that. This was in the last century. Now it is science and research and technology that drive the relationships and exchanges between countries. So research universities now find themselves right in the middle of all the most exciting developments.

After almost 30 years in the classroom, are you a little surprised to find yourself in this office now?

[Laughing] Obviously, I mean, look at me [pointing to his t-shirt]. Do I look like someone who wanted to be a VP? Never in my life, man, but here I am. It was a big surprise to me—first, that I would even apply and, second, that they would take me [Laughing]. That being said, this is the best job in the world.

What do you miss most about your old job?

As a professor, you have almost complete control of your days. You do what you want, when you want. If I want to go to the dentist, I go to the dentist. But in this job, going to the dentist is an incredible challenge. I make an appointment and I have to change it five times because things keep coming across my desk marked "Urgent," "Important" and "Priority" and I have no control over that.

I was in computer science with a bunch of freaks like me. We all arrived here at around the same time, in the mid-70s and we've been together for almost 30 years. Now, I have to organize my time just to see my old friends.

Your love of the Tintin comic book series is well known. You were a child celebrity in Quebec for winning a TV quiz show about it. What's the attraction?

Quality and excellence. It's been translated in just about every language and people all around the world have been reading it for 75 years. I still read Tintin. My father, who is 91 years old, still reads Tintin. My children read Tintin.

Would Tintin be a good researcher?

He's got the curiosity, for sure. But research isn't just that. Yes, a part of it is ideal because this is what drives your passion. But at the same time, this is reality, not a comic book. You have to put in the hours. What was Edison's formula? Ten percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration. The fact that you love what you do doesn't change the basic reality that, if you want to compete with the best in the world, you have to be ready to work very hard.