Talking the talk: McGill a force in language studies

Talking the talk: McGill a force in language studies McGill University

User Tools (skip):

Talking the talk: McGill a force in language studies

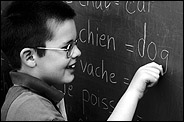

Though French immersion programs continue to gain in popularity across Canada, the process of learning a language is still not completely understood. A new program at McGill will go a long way to correcting that shortfall.

|

|

Started last semester with a group of eleven students, the new interdisciplinary PhD in Language Acquisition builds on McGill's internationally recognized leadership in the field of language development.

"McGill has a great deal of strength in the area of language research," says psychology professor Fred Genesee, director of the Language Acquisition Program (LAP). The Departments of Psychology, Linguistics and Second Language Education and the School of Communication Sciences and Disorders all have researchers who specialize in language acquisition.

"We thought that by highlighting the talent related to language acquisition that is distributed in these departments, it would allow us to promote this strength that we have," says Genesee.

The new program is the only one of its kind in North America. As it is interdisciplinary, students enrol in a PhD in one of the four participating units, and they must complete all the requirements for that degree. In addition to this, they attend a monthly seminar on language acquisition, and their thesis committee must have at least one member from one of the other participating departments.

Though the LAP is new, it is not the first time that many of the professors participating in the program are working together.

"There was a group that started in 1996," says Genesee. "We had been collaborating and getting grants together for quite some time."

The LAP, drawing as it does on existing resources, has proved to be an affordable and flexible way to set up a new program.

"It created a critical mass of professors that could be shared between departments without a lot of new hires," says communication sciences and disorders professor Martha Crago.

"If one department tried to do this, there wouldn't have been as many hires," she says.

Even without a specialized program in the area, McGill has become one of the leading institutions in the world for language studies. A survey published recently by the Boston University Conference on Language Development noted that, in terms of presentations at that highly regarded conference, institutions such as Harvard and MIT were "decisively muscled aside at the top by McGill."

"There's a history (in language studies) at McGill that goes back all the way to Penfield and Wallace Lambert," says Crago. "Over the years we've attracted a lot of good researchers and produced a lot of good researchers."

McGill's strength in language acquisition can be attributed to many things, including the distinguished history connected to neurologist Wilder Penfield and psychologist Wallace Lambert. Lambert's work on the benefits of bilingualism for children, for instance, have often been cited by proponents of language immersion programs.

Genesee believes McGill's geographic location may have something to do with it as well.

"It may be the context of McGill, being in this complex linguistic environment," he says. "There's a very good research lab all around us."

Of course, other universities in this "lab" take advantage of it as well -- which led to the recent creation of the Montreal Network for the Study of Language, Mind and Brain -- a group of researchers from Concordia, McGill and UQAM with disparate approaches to language and language studies.

This group, led by communication sciences and disorders professor Shari Baum, was recently awarded a $3.2-million Canada Foundation for Innovation grant that will allow them to equip their labs with the latest equipment, such as a digital video recording studio, to which the LAP students will have access.

"All of the members of LAP are members of the network," says Baum. "Anyone who comes to that doctoral program will have the opportunity to make use of the state-of-the-art equipment."

In a very practical sense, language acquisition is an important area of human studies, and because of French immersion programs, a controversial one in Canada as well.

"A lot of language acquisition takes place in a school context," says second language education professor Roy Lyster. "My own research is very classroom based."

Second language immersion programs are controversial because it is feared that students will not learn as fast in a second language, or lose full competency in one language or both. Researchers like Lyster try to inject some observational data into the debate.

"My own research is language learning out of context," he says. "I'm interested in how teachers can teach science and math and still focus on language."

Genesee's research debunks the idea that learning two languages is harmful to a child. Often, he says, parents who spoke two languages were advised to only speak one or the other to their child in order not to confuse them.

"Many people think that there are risks or costs involved," says Genesee.

Previous research had indicated that children only have one language "system" of grammar and vocabulary. Learning two languages would harm the child's language cognition.

"The idea was that the child would have a system that is comprised of French and English," says Genesee.

In fact, according to Genesee, they can accommodate many language systems, and the way they interact is quite complex.

"If, for instance, they mix French into English, they follow the English grammar," he points out, which indicates that even if the vocabulary occasionally mixes, the languages do not.

For obvious reasons, much of the best known language research at McGill focuses on English and French, though Genesee and Crago are both working on a study of how Inuit children learn language. Psychology professor Laura Ann Pettito, another member of the LAP team, recently published a heralded study that indicated that deaf people who use sign language process very specific parts of natural language (like words and parts of words) at the same highly specific brain sites as hearing people do with speech. The variety of approaches and techniques now available to the students and professors of the LAP since its creation is a great thing, according to Lyster.

"Being exposed to faculty and students outside of education, I think they'll have a better sense of the multidisciplinary nature of language acquisition," Genesee says of his LAP students.

"I feel pretty excited about this."