Cyanide and sin

The stylized visual world of '50s true crime magazines

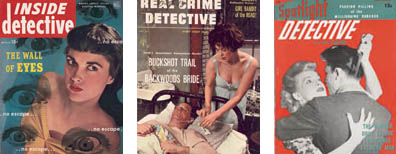

Though there have been coffee-table books on lesbian pulp fiction of the 1940s, cheesecake pin-ups of World War II and classic film noir posters, the stylistic evolution of the quintessentially American true crime genre has been overlooked until now. This month, communications and art history professor Will Straw launches Cyanide and Sin: Visualizing Crime in 50s America in New York City and Montreal.

Thanks to a compulsive five-year eBay habit, Straw has amassed boxes of Inside Detective, True Mystery, Men in Danger and the like. He sifted through that private collection for the nearly 200 images reproduced in the book. "I wouldn't be here as a McGill professor if I weren't a comic book geek who got into movies, then film studies," said Straw.

Straw writes about the history of the true crime genre, explaining that broadsides, then penny press papers, covered criminal activities since the 17th century. True crime magazines only emerged in the post-World War I boom, born of confession magazines like True Story. In 1924, Macfadden Publishing started True Detective Mysteries, then Fawcett responded with Startling Detective in 1927. The next two decades would see dozens of fly-by-night companies enter the field.

The late '40s were marked by melodramatic studio photo shoots and flamboyant paintings. True crime mags hit their design stride in the '50s, when compelling imagery met with a bold creative layout and colourfully portrayed dames gave way (but not entirely) to the gritty chic of black and white photography.

Until 1960, Straw writes, true crime magazine design "soaked up the styles of tabloid journalism, film noir, New York street photography, Surrealism, American urban realist painting, revolutionary montage and innumerable other currents criss-crossing American culture."

The '60s covers turned to lurid colours, embracing psychedelic effects as well as a near-pornographic coverage of gore. Then the circulation of true crime magazines waned, with Startling Detective putting out its last issue in September 2000.

The '50s are Straw's main focus, and he attributes the avant-garde design to America turning away from sentimentalism. "So much imagery of the twentieth century is about suspicion and danger, about finding an edge, a sense of menace, because it didn't look corny like a Norman Rockwell," he said. Historians are beginning to recognize that the '50s were a time of major changes in sexual and social values, and "true crime magazines capture something of this stirring below the surface."

"There's been an incredible resurgence of true crime culture over the last decade — the police procedural television programs, the true crime paperbacks, the websites, and so on," said Straw. "The cute and romantic detective couples or playboy lawyers of earlier decades are gone. We turn to the true crime genre to test the limits of what we can stand, part of a general condition in which music, sports and television programs have to be 'extreme' in some way to stand out."