Shedding light on rare genetic disease

Shedding light on rare genetic disease McGill University

User Tools (skip):

Shedding light on a rare genetic disease

At just 11 months old, Ron and Nicole Hutchison's daughter Mackenzie had her first epileptic seizure. The next day their pediatrician told them that kids, "just have seizures" and not to worry about it. After a second seizure that night, the Hutchisons rushed Mackenzie to the local hospital in Southern Ontario, to be told that they'd have to wait six weeks for a CAT scan. Through connections, Ron was able to get Mackenzie in for testing at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children within a few days, where it was revealed that their daughter has Tuberous Sclerosis (TS).

"I'd never heard of the disease, my wife never heard of it. The first question is 'Is my daughter going to die?'" he said.

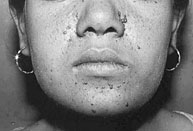

Although TS, previously known as Bourneville's disease, affects one in 6,000 to 10,000, few people know about the genetic disorder that can wreak havoc throughout the body, causing epileptic seizures, mental retardation and behavioural problems. The name comes from the tuber (or root vegetable)-like tumours that grow in the brain and other organs such as the kidneys, heart, eyes and lungs. TS is also characterized by specific skin lesions, such as a rash-like mask over the nose and cheeks or depigmented ash-leaf shapes, often the clinician's first clue to the disease. There is no cure.

Adenoma sebaceum, a sign of Tuberous Sclerosis

Hutchison was in Montreal in December to attend the International Symposium on Tuberous Sclerosis: Genetic, behavioral and surgical aspects, held at the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI).

During an interview with the Reporter, Hutchison showed a photo of his three-year-old daughter, a cute round-cheeked strawberry blonde playing in the fall leaves. "My daughter has three tumours on her brain, multiple lesions on her kidneys (which could lead to failure). Luckily her heart has been cleared. She has multiple tumours on the back of her eyes."

The conference brought together over 20 experts from North America and Europe to discuss this rare disease. It was organized by the husband-and-wife team familiar to the world's neuroscientist community, Eva and Frederick Andermann. Both McGill professors of neurology and neurosurgery, Eva is head of the neurogenetics unit of the MNI, as well as a professor in human genetics, and Fred is the coordinator of MNI's Epilepsy Service and Seizure Clinic, and professor in the department of pediatrics.

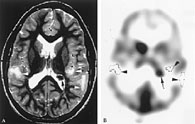

MRI and PET images of the brain of a nine-year-old boy with TS

"The conference focused on important progress in the study of gene mutations, the hitherto unrecognized behavioural aspects of the disease, and the possibility of detecting the tubers that cause the epilepsy and removing them surgically," explains Eva Andermann, who started studying the disease over 20 years ago. The conference brought together researchers from numerous disciplines: neurology, neurosurgery, psychiatry, genetics, neuroimaging, pathology, and molecular biology.

Hutchison's a board member of Tuberous Sclerosis Canada Sclerose Tubereuse (TSCST), a group started in 1990 to raise public awareness of this disease, and provide support. He came to town with Nancy Bryce, president of TSCST. Her eight-year-old granddaughter, Haileigh, has TS. In both Haileigh and Mackenzie's cases, the TS was a spontaneous mutation, meaning there was no genetic precedent in the family.

Although lay societies such as TSCST are invaluable and, in part, responsible for the coordinated research effort of scientists, Andermann says that public support for and awareness of the disease is still low. She attributes this in part to the stigma of epilepsy, one of TS's main symptoms. "I don't know if you have to be in a wheelchair to get sympathy," she says, clearly frustrated with our society's prejudice. "Almost everyone knows someone affected by epilepsy."

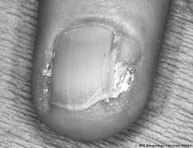

Typical characteristic of Tuberous Sclerosis: angiofibroma

Hutchison says that some forms of TS-related seizures can do far more developmental damage than other epileptic seizures, which means that during an episode every moment before treatment counts. For a while, Mackenzie was having 20–25 obvious seizures a day, and has had about four massive ones. The Hutchisons thank their cat for alerting them to one of Mackenzie's worst seizures. One night, after they'd already gone to bed, their cat, Boston, kept them awake by "crying and crying," Hutchison said. "I got up and checked on Mackenzie. She was blue, there was vomit everywhere, [and] urine."

"You're constantly waiting to respond to crisis," Bryce said of having kids with TS.

Parenting a child with TS is fraught with trying to untangle which behaviour is the child's and which the ailment's. For example, Bryce remembers Haileigh having a lot of fear and anxiety about going to sleep. Was this just normal ornery childhood behaviour? The family later learned that sleep disorders can be a TS symptom, and Haileigh may have been having small seizures at night. Now that surgery has removed some of the tumours, she sleeps soundly.

Half of the MNI's conference was devoted to the surgical treatment of TS-related epilepsy. Traditionally, drugs have been used to control the seizures. Since the late '90s, it's been recognized that surgical intervention to remove major tubers in the brain can work wonders, Fred Andermann explained. Tubers associated with epilepsy can be mapped out through clinical means and a variety of brain imaging techniques, then each case is evaluated for surgery.

Typical characteristic of Tuberous Sclerosis: periungual fibroma

The genetics of the disease was also a major focus of the conference. Either of two genes explain at least 80 percent of cases: TSC1 and TSC2 (Eva Andermann adds that there is possibly a third gene). The first gene took over a decade to locate. "Because of the large size of the genes and hundreds of possible mutations, it's a real research effort to test for TS," she says.

Fortunately, cross-continental teamwork between researchers has eased the load.

A few years ago, Eva Andermann had identified a large French-Canadian family with TS, in which the seizures occurred in childhood and then remitted spontaneously — an almost unheard of phenomenon with this disease. Andermann wondered if this was a new strain of TS, or a new disease entirely. Collaboration with Harvard's David Kwiatkowski helped discover that the family had the TSC2 gene, which was a great surprise given that TSC2 was hitherto associated with severe cases. In Rotterdam, Erasmus University's Ozgur Sancak, a PhD student of Dicky Halley, also found a family and several sporadic cases with the same mutation, and the three schools are pursuing the genetic puzzle together.

Such research can lead to prenatal testing and counselling for families on the likelihood of passing on the disease. As well, once researchers pinpoint a gene mutation, they can artificially copy it and study the function of the mutated protein — what it can or cannot do. "This collaboration alone is worth the whole effort [of the conference] and will extend our knowledge of gene expression," Andermann says.

Although specific gene therapy is still far in the future for neurological diseases, the field of pharmacogenomics is "in full swing," Andermann says. Once researchers find out what function a gene is lacking, they hope to develop a drug that can specifically correct this.

But all too often, even medical professionals are ignorant of TS. "It's frustrating as a parent to explain what it is to the physician," Hutchison said, recalling trying to tell an ambulance dispatcher his daughter had Tuberous Sclerosis only to have her insist he meant tuberculosis.

The lack of awareness of the disease means that children who are diagnosed with autism or epilepsy may have TS, but never be properly diagnosed. The better informed that people are about the disease, the more likely it is that kids will receive treatment early enough to make a difference.

In an email to the Reporter, Bryce wrote that she took succour in the effort by conference participants to come to a consensus on the treatments and management of TS. The frustrations and hardship for parents of kids with severe versions of the disease mean "it's a grieving process that goes on since diagnosis."

Other TS researchers at McGill who participated in the conference include autism specialist Eric Fombonne; neurologists François Dubeau and Bernard Rosenblatt; and neurosurgeons André Olivier and José Montes. For more information, go to www.tscst.org.