P.O.V.

In the cycle of evil

On why speaking about genocide matters—globally

I consider myself extremely fortunate. My early childhood meant growing up in communist Yugoslavia: a relatively free, fair and tolerant society, where "Brotherhood and Unity" was the official ideology. That is, until former President Slobodan Milosevic got cranky and all high on power, starting to dig up bones that had lain for centuries, touring sacred sites and telling a narrative powered by myths of the other, involving the Ottoman Turks, the Albanians, the Bosnian Muslims. The masses happily obliged to his call, turning into a pack ready to break loose at first command.

TZIGANE

It is not merely the fact that Milosevic came about that is worrying. His dreams of "ethnic cleansing" were, ultimately, almost a century old. What is worrying is the fact that Milosevic was so quickly able to enchant the Serbian people in Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina—and receive their full support for his murderous adventure. Those who disagreed with him, like former President Ivan Stamboli, were swiftly disposed of in true dictatorial style.

In the Shoah, at least three quarters of the Jewish population in Yugoslavia perished and in the "Independent State of Croatia," leader Ante Paveli's regime used its power to turn on the Serbs, and a large number of them perished in a brutal, genocidal campaign. The post-war idea of "Brotherhood and Unity" helped nurture the "fragile ethnic balance" and the "G-word" was swept under the carpet. Silence keeps a society from questioning and understanding its past. In a way, it was this silence that had kept Yugoslavia traumatized and allowed for genocide to repeat, less than half a century on. In today's Bosnia, the "G-word" was forced out of the schoolbooks, for fear of "harming the national balance." Rather than dealing with the—inconvenient—truth, we were told once again that, for the sake of togetherness, it's not a good idea to learn from the past.

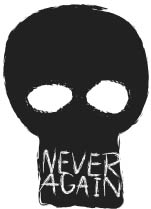

The international community has allowed the "never again" utterd loud and proud in 1945 to become, to quote historian Deborah Lipstadt's blog, "again and again and again." The world hasn't learned from an all-day tour on the murderous cycle: ignoring what went on in Cambodia, East Timor, Guatemala, Iraq, and elsewhere; turning a blind eye in 1992 to the distress call from Bosnia; turning both eyes blind to the pleas by LGen Romeo Dallaire, and even today, the world's bureaucrats are more preoccupied for new, inventive terms to describe—rather than stop—the Darfur genocide.

Conferences such as the upcoming Global Conference on the Prevention of Genocide, hosted by McGill, are a necessity in today's world: the vision of Polish lawyer and anti-violence advocate Raphael Lemkin was, 60 years ago, to free the world of genocide. There's no doubt that we've failed Lemkin. We've failed all those millions who have been slaughtered in genocides worldwide. Therefore, experts, survivors and policy-makers must initiate a global effort to prevent genocide. Prevention can only work if we think of it in a sustainable fashion, which is why the presence of the young leaders at the conference—and at their own, pre-conference forum—is a key element. I am extremely fortunate to be one of these young leaders.

I am of Bosnian Muslim and Jewish ancestry. My relatives on both sides, including my great-grandfather and my mother, shared the same tragic fate of being targeted merely because of their identities. Here, too, I consider myself extremely fortunate—I am still around, and as long as my voice serves me, I have to join those standing up to prevent genocide. In the hope that, tomorrow, "never again" can truly become—never again.

Muhamed Mesic works as a Research Fellow for the Institute for Research of Crimes Against Humanity and International Law of the University of Sarajevo. He will be participating in the International Young Leaders Forum in conjunction with McGill's Global Conference on the Prevention of Genocide.