| ||

| ||

|

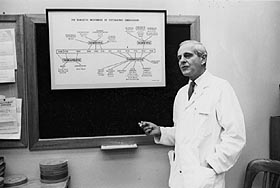

Heinz Lehmann On April 7, 1999, Canada lost one of its pioneers in psychiatry, Heinz Lehmann. Born in Berlin on July 17, 1911, Lehmann arrived in this country in 1937, and began practising psychiatry in a place where few chose to work: Verdun Protestant Hospital, now called the Douglas Hospital. There, he rose quickly through the ranks, becoming clinical director in 1947. In the '50s, Lehmann became world-famous due to his pioneering work on chlorpromazine, a drug for schizophrenia -- but he never claimed originality for this contribution. Thoroughly trilingual, Lehmann regularly read European journals where he learned of the work of Delay and Deniker, French pharmacologists who developed the first psychotropic (behaviour-calming drugs without the sedative effect of barbiturates) drugs. Chlorpromazine, for instance, allowed those suffering from schizophrenia to leave mental hospitals where, previously, they had to be institutionalized. Lehmann was also one of the first psychiatrists in North America to introduce imipramine for the treatment of depression. Lehmann published over 300 scientific papers, most concerning psychopharmacology. He won many prizes, ranging from the Albert Lasker Award in 1957 to his recent election to the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame in 1998. He was also a companion of the Order of Canada. At the Douglas, Lehmann became research director in 1962, and director of medical education in 1967. In 1970, following the retirement of Robert Cleghorn, he agreed to serve as chair of the McGill Department of Psychiatry, a post he held until 1974. In 1976, he founded a Division of Psychopharmacology. From 1981 until his passing, he also served (without salary) as deputy commissioner for research, New York State Office of Mental Health. Beyond his scientific achievements, Lehmann was also famous for his humanity and simple way of living. He lived with his family for many years in a house on the grounds of the hospital. In spite of the distance between the Douglas and downtown Montreal, the psychiatrist was renowned for never owning a car, and for bicycling everywhere. With hundreds of patients to take care of at the hospital, Lehmann developed a reputation as an unusually dedicated clinician. He also initiated a practice that he continued to the end of his life: on Christmas Day, he and his son François, now a family physician, would tour the hospital and offer holiday greetings to every patient. In fact, Lehmann continued working for as long as possible, seeing patients until about three months before his death. An idealist who lived a life of service to those who were sick and marginal, Lehmann served as a wonderful teacher to generations of students, many of whom will remember his films about psychopathology -- the material from which became the basis of chapters in Kaplan's Comprehensive Textboook of Psychiatry on the clinical features of schizophrenia and mood disorders. The Department of Psychiatry will hold a memorial service for Dr. Lehmann later in the year. Joel Paris, M.D.

|

|

|

| |||||