| ||

| ||

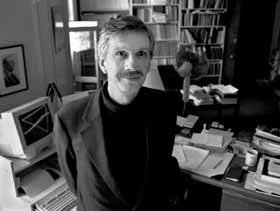

| Battered Red Cross looks to the future |  PHOTO: OWEN EGAN |

|

DANIEL McCABE | The tainted blood scandal of the 1980s In the wake of the scandal, the organization is being stripped of its role as the country's official blood agency McGill law professor Armand de Mestral is the newly elected vice-president of the Canadian Red Cross and he will be a principal player as the 100-year-old organization fights to stay alive. "Words can't express our great sorrow over being a part of this immense tragedy," says de Mestral. Still, he says it's unfair to make the Red Cross the whipping boy for all that went wrong. "All the decisions that were made were made in collaboration with the government and frequently under the direction of the government." De Mestral has been involved with the organization for four years "In a sense, our responsibility for the blood system has been holding us back," says de Mestral. "Every board meeting I can remember attending has been dominated by the blood system. We always had a sense that there were other things we ought to be doing, other issues we should have been discussing, but there was never any time. Now we won't have any excuses." De Mestral says there is no shortage of ideas for new directions. The Red Cross currently organizes part-time nursing care for thousands of patients in Ontario and New Brunswick. "As the health system changes, maybe we can make a greater contribution in this area in other provinces. "One thing that I would very much like to see is for us to build more links with native communities throughout the country," says de Mestral. The Newfoundland Red Cross provided emergency assistance to the suicide-ravaged community of Davis Inlet, but de Mestral thinks much more can be done. "Natives want more control over their lives and we can help in the areas where we have expertise. We can train young people in first aid, in water safety, in emergency relief techniques." The Red Cross's ability to provide emergency relief has been a saving grace for the organization in recent years. Pilloried for its role in the blood crisis, the agency has also been hailed for its relief efforts for flood victims in the Saguenay and in Manitoba. Still, de Mestral says this area also needs to be re-examined. "We haven't taken into account the ecological catastrophes that I'm afraid we'll be seeing more of And the Red Cross isn't getting out of the blood business just yet. The organization will likely continue to play a leading role in the collection, testing and distribution of blood products for Quebec Transferring its blood responsibilities to the new national agency will probably take a year and the Red Cross will maintain its current role until the handover is complete. That means the organization may again face challenges from students at donor clinics set up on university campuses. The Red Cross cancelled last year's McGill blood drive in response to a protest led by then-president of the Students' Society, Chris Carter. At issue is the questionnaire distributed to prospective donors. Men who say they have had sexual relations with other men are rejected as donors. Some argue that this discriminates against gays, and that the Red Cross should target risky sexual behaviour (sex without condoms) instead of gay relationships (even when safe sex is practised). De Mestral says he is making this issue a personal priority. "University blood clinics have traditionally been very effective With the help of a former student, he will develop a communications campaign aimed at explaining the Red Cross's reasoning to students across the country. "We have no choice but to ask the questions we ask. It's required by law, for one thing. The new agency will ask the exact same questions once it's in operation. If we didn't ask these questions, we would be regarded as negligent The problem with asking only about unsafe sexual practices instead of about gay sexual practices, says de Mestral, "is that you presume that everyone has the medical knowledge to answer those questions correctly." Mistaken assumptions could lead to serious consequences, he says. Someone might consider himself a safe donor if he has unprotected sex, but still tests negative for HIV. "What about the window period during which a test wouldn't detect HIV? Someone could have just received a good test result and still unwittingly pass on the virus, thinking that what they were doing was safe." De Mestral is still teaching three days a week at McGill and working with his graduate students. He credits his dean for giving him the leeway to take on his new role at the Red Cross and says there is a lot of work to be done. "Wherever we look, we can see challenges that need to be addressed. We exist to help the vulnerable and there is no shortage of areas where we can make a contribution."

|

|

| |||||