Sounds of the future

Music and technology meet in new building

It is pronounced Kermit, like the frog, although a better comparison could be made with an octopus.

The Multi-Media Room is an entirely soundproof acoustic research and recording lab.

Saucier-Perrotte

The Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music, Media and Technology, better known as CIRMMT, has its head in the gleaming new music building at Aylmer and Sherbrooke Streets.

Its tentacles reach beyond its lair to other McGill departments and faculties, as well as to the Montreal Neurological Institute, the Université de Montréal and the Université de Sherbrooke.

"The key word of the CIRMMT acronym is interdisciplinary," says Stephen McAdams, the Texas-born and California-raised expert in music perception and cognition hired away from Paris to head the centre, which opened in 2001. "We are trying to create an environment where people from different disciplines complement each other and solve problems they couldn't have solved - and imagine new avenues of research they couldn't have thought of - before the disciplines came together."

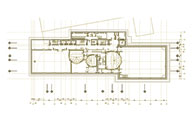

Architectural plan of the control rooms for the recording studios. The Multi-Media Room is on the far right.

Saucier-Perrotte

From the Department of Psychology come Carolyn Palmer and Dan Levitin, both interested in the psychology of hearing. From the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering comes Jeremy Cooperstock and from Instructional Multimedia Services comes John Roston, whose mission is to use computers to create state-of-the-art videoconferencing.

BRAMS connection

The main off-campus link is with BRAMS, a neurological research group (the name is a contraction of brain, music and sound), which is headquartered at the Université de Montréal and co-directed by McGill professor Robert Zatorre of the Montreal Neurological Institute and Isabelle Peretz of the psychology department of the Université de Montréal.

Exterior of the new music building on Sherbrooke St.

Owen Egan

BRAMS will do most of the work involving electroencephalography - think of brain-imaging electrodes attached to the skulls of subjects happily listening to Beethoven. This is intended to complement the McGill emphasis on the theory of music perception and cognition.

The Université de Sherbrooke provides CIRMMT scientists with expertise in acoustics as a subset of physics. Hard-science types like Alain Berry will work with the sound engineers (Tonmeisters is the German word) from the famous McGill Graduate Program in Sound Recording.

The encounters could be interesting. McGill has traditionally regarded the practice of recording Beethoven and Stravinsky, or Brian Eno and Harry Belafonte, as primarily a matter of art rather than science.

21st century group

Stephen McAdams, director of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music, Media and Technology

Claudio Calligaris

In many respects CIRMMT blurs that venerable demarcation. The CIRMMT offices and laboratories in the new music building are outfitted in 21st-century style, all sleek lines and neutral colours. No one would confuse this oak-and-aluminum place with the Moscow Conservatory.

To be sure, the addition of a 200-seat recital hall will be welcomed by most Montreal music lovers as a fine place to hear graduate recitals and chamber music. But McAdams foresees issuing wireless Palm Pilots to members of the audience so they can register their personal reactions to the performance in real time.

"Why does a broad crescendo have such a great, dramatic effect?" he asks, by way of supplying a hypothetical example of a typical CIRMMT investigation. "What is going on acoustically? What is the perceptual and emotional impact of that kind of thing?"

Watching and listening

Stairwell leading to the Marvin Duchow Music Library

Owen Egan

Likewise, the aspiring Callases and Carusos of Opera McGill will be pleased to avail themselves of the new Opera Rehearsal Studio in the basement of the new building. And CIRMMT will be watching, with cameras and sensors, to learn more about how singers move and breathe. The object will be to add some rigour and stability to the pedagogically intuitive (not to say chaotic) area of vocal instruction.

Adjoining the rehearsal room is the CIRMMT holy of holies, a four-story, acoustically isolated black box - the finest facility of its kind in the world for sound recording and research. The room will not only accommodate a full orchestra and choir (music dean Don McLean has already talked to Kent Nagano, the future Montreal Symphony Orchestra music director, about the possibilities) but also will be outfitted with screens and a control room to make it appealing to movie soundtrack producers.

Hexagram, a Concordia-UQAM media arts collective dedicated to video, dance and theatre, has already expressed interest.

This Multi-Media Room is at least a $15-million donation and one custom-built control room away from completion, so many of the publicly glamorous projects - soundtracks and MSO recordings - will not be under way before 2006-2007. The smaller laboratories on the top floors will be outfitted by spring and available to researchers.

Pioneering work

The 200-seat recital hall is by ARTEC, world leaders in acoustic design

Saucier-Perrotte

CIRMMT is dedicated to and a pioneer in the thoroughly modern practice of telepresence, the internet transmission of music audibly, visibly and in real time. Telepresence allows a violinist in Montreal to play a Mozart sonata with a pianist in Sydney. "You want one person to feel that the other is right here, not half of a world away," says McAdam. "That means you need high quality. The better the quality, the better the nuances that people are able to communicate."

Montreal was a natural place for CIRMMT to materialize, not only because of the unusual concentration of universities in and around the city but also because of the progressive character of the faculty itself. Any genealogy of the new centre would recognize the Sound Recording Program (founded by Wieslaw Woszczyk in 1979) and the Music Technology Group (started by Bruce Pennycook in 1987) as the direct forebears of CIRMMT.

Of course McGill's stature as a broad-spectrum university was helpful. The combination of Montreal and McGill brought McAdams from the Institute de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM) the notorious subterranean Parisian centre opened in 1977 by the French composer Pierre Boulez as a nexus of all things sonic and progressive. One short way of describing CIRMMT is as the new IRCAM.

Wide-ranging applications

The immediate output of CIRMMT will be knowledge, but technological applications and even commercial products are on the horizon. McGill is not specifically interested in commercial product development, but it is conceivable that CIRMMT advances will generate a better surround-sound system for your recreation room or a more realistic delivery in the cinema. One CIRMMT project involving the D-Box motion stimulator firm is a souped-up version of the soundtrack of the movie Master and Commander, complete with vibration, pitch and roll.

McAdams foresees the emergence of new kinds of sound controllers, say an ultra-refined mixing panel activated by a mid-air gesture rather than the flip of a switch or the turn of a knob, or a motion detector that turns movement, such as dance, into music.

Another obvious and explosive growth area is the internet. Most recorded music acquisition now is illegal. Only a small percentage is paid for. Will CIRMMT broadband research result in a new way of bringing music legally to the market?

New avenues built on excellence

To anyone who asks whether the faculty is diverging from its forte as Canada's best professional musical training school, McAdams says the answer is no. The faculty is at the forefront of integrating traditional study with new vistas.

"How many people are buying hand-built Steinways and how many are buying Fender Rhodes keyboards and Yamaha synthesizers?" McAdams asks. "The segment of the industry that has gone digital is enormous. Music is changing and technology is playing a strong role."

This is no time to embrace the past, McAdams says.

"Montreal has become the mecca of music technology and music psychology. Now those two are coming together and making something really incredible."

Arthur Kaptainis is the Gazette's classical music reporter