The ebb and flow of the McGill Bookstore

The ebb and flow of the McGill Bookstore McGill University

User Tools (skip):

The ebb and flow of the McGill Bookstore

Phillip Todd dons a red vest to battle the back-to-school book-buying frenzy

Tidal waves.

It's no surprise the metaphor keeps surfacing when McGill Bookstore employees try to describe the tsunami of students that flood into the basement of the McTavish St. store the first week of class.

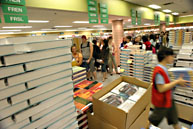

It's only 11:30 am on day one of lectures, but already students are pouring in by the hundreds.

Wave upon wave of McGill students crashes down the stairs into the bookstore's basement textbook department, breaking against the information desk and spreading out into the aisles of biology textbooks, political science coursepacks, English novels and more. They're hunting for their course material with Ahab-like determination — and they're ready to pay a Moby Dick--size price for their catch.

The scrape of boxes being taped shut and the wooden thud of books bumping shelves is torpedoed by yells of "Next!" as a fleet of cashiers compete for the attention of the next impatient customer.

A sales line carves its way across the basement floor and streams behind the staircase as cashiers race to shorten the wait.

Meanwhile, a crew of red-vested shelvers works the floor, fielding questions about missing texts, funnelling puzzled students to the proper shelves, ferrying textbooks from box to skid and from skid to shelf.

Owen Egan

Buzzing about in the melee, the first hand on deck navigating this September storm is the bookstore's frenetic, bespectacled floor coordinator, Patrick McGovern.

McGovern is in charge of making sure that enough employees are on the floor to stem the tide of students' queries, that the sales line is flowing smoothly and that all textbooks are where they should be on the shelves.

Not quite out of breath but close, he finds me at the back of the store. As McGovern explains sales have, that morning, already reached an estimated $300,000, a red-vested blur slaps a paper bag into the floor coordinator's chest and vanishes behind the stairs.

"My breakfast," McGovern says, his worry lines giving way to a smile, perhaps his first this morning.

"The store as a whole started slow," he admits. "[The number of customers] spiked straight up and we didn't have as many employees as we should have."

In terms of business, "today is a Thursday instead of a Tuesday," he says, comparing the day's pandemonium to the bookstore's first week in previous years.

I decide not to correct him and tell him it's Wednesday. The man clearly has too much on his mind to be troubled with such details. "I'm a bit wired today," he says, before disappearing back into the fray.

I head back up the stairs and stop one more time to survey the turbulent waters below.

I take a deep breath. Tomorrow morning I will report for work.

When I arrive for work in the morning at 10:30, Wednesday's tempest of trade is gone. An unsettling quiet fills the basement. No more than fifty students peruse the aisles in search of their texts and the sales line is down to a trickle. Even the red vests are moving sluggishly.

With no customers to help, I peruse the shelves trying to look busy. Amid stacks of 1,800-page volumes of The Complete Works of Plato, 650-page editions of Contemporary Linguistic Analysis and political science texts with titles like International Order and the Future of World Politics, I suddenly feel very small.

The stillness of the room was heavy with the inevitability of the crush.

"We're actually a little worried; it seems too quiet," says McGovern shortly after I arrive. But even "if we have no sales up till 11 am, it still means we're going to do $750,000 worth of sales" that day, he cautions.

He was right: the morning's tranquility turns out to be but the calm before the storm.

By noon, the sales line extends to the back wall and behind the stairs, a length it will remain for the rest of my five-hour shift.

"(The rush) is pretty stressful," says clerk Aliyana Traison, a veteran of the start-of-term frenzy who has worked for the bookstore since June 2002.

"People buying and selling and returning books. Profs calling to say 'I forgot to put an order in.'"

"You want to say, 'This is not the best time right now,' but you've got to deal with it."

As a student, working for the bookstore offers certain advantages, Traison says.

"Whenever I come in here [at the start of term], I know every single book that's available. It helps me decide on my classes," says the U3 History student.

This knowledge also gives Traison the superpower-like ability to tune into any conversation she hears on campus about a particular course.

"When people talk about their classes, I know what books they're reading."

There's an easy way to spot which bookstore shelvers are being run ragged. Their red vests have drooped to one side, giving them the look, at best, of having a slight slouch, at worst, a hunched back.

Owen Egan

Ranya Elsadawy no doubt started off her shift as I did, with the vest upon her shoulders, the picture of symmetry.

But by 1 pm, as we guide a relentless flow of management students to the texts in our aisle, neither of us is much concerned with our grotesquely gibbous appearance.

"It's my first day and they put me in the busiest section," she says. "They all come at the same time for the same books. It's a wave."

The U2 Civil Engineering student may be frazzled. She may have pointed out the textbook Information Systems enough times in the last hour to reasonably lose her cool. Yet she's still cheerful.

After spending a summer monitoring Quebec highways via video-link for the provincial government, Elsadawy says it's nice to have a job where she can work with people.

Elsadawy is one of 60 employees, many of whom are students the bookstore hires through a temporary employment agency between September 1 and September 19 to help with the rush. Like others, she took the job to make some cash before the term's workload kicks in.

After the rush, only 11 students are needed to staff the entire bookstore, according to assistant manager Adriana Gabriel.

Of the temporary workers, 24 don red vests and work the floor in the textbook and stationery departments. The rest form the fleet of cashiers who, each shift, face the relentless, unforgiving stream of thousands of McGill students.

Around 2 pm, McGovern has sensed a problem with the sales-flow.

"The line is moving too slowly: we need people to help bag books," he says, charging around the basement plucking red vests, myself included, from the aisles and sending them over to the cashiers.

I take a place beside one and start bagging books for customers.

Cashier Anita Wo is polite, friendly — and ruthlessly efficient.

Every two minutes she sends a new customer up the stairs gripping a McGill Bookstore trademark-red plastic bag.

As if by reflex, she strains forward, arm raised to catch the next one's attention.

Next!

Moments like this are what Wo loves about her job.

"I like the stress. I'm the one who raises my hand the most," says the U3 Management student. "I like it when it's fast, fast. I like doing many things at once," she says waiting for a receipt to print. Her body is edging forward, ready to call her next customer.

"I like that you only work for two or three weeks."

Over a dozen students pass before us in the next half an hour.

Many cringe at the sight of their bill — most bills are over $200; many twice that much.

One student spends his last $100 on books for class. Another racks her brain as she tries to remember why her credit card is maxed when she thought she had it all planned out so perfectly.

"No one should not take this course because they are intimidated by the cost of the books," says history professor Gil Troy standing before 170 students attending their first class of the history of U.S. presidential campaigning.

"I urge you to find creative ways to share costs."

Troy is addressing one the foremost issues on students' minds when they descend into the basement of the McGill Bookstore.

Besides exchanges about where to find a textbook, the next most asked questions regard the hefty price tags attached to many texts.

While many students have no choice but to fork over for expensive books, others will hold out for weeks in hopes of finding a second-hand copy or an earlier edition at used bookstores such as The Word on Milton St.

Owen Egan

While McGovern admits pricing can be a "nebulous area," he says the prices are fair and adds the bookstore always sells texts at the manufacturer's recommended price.

"Would I think the prices are fair? Keeping in mind it's a business, yes," McGovern says.

"I can't think of any books here that have had an unfair markup."

The professionals who write textbooks need to be enticed with a reasonable financial reward, he adds.

There is, however, an effort to keep the financial realities facing students in mind, he says.

The bookstore encourages students to sell back used books, which are then resold at a reduced price. If ever a subsequent order of books arrives and the publisher has since lowered the price, students who paid the higher amount can be reimbursed the difference by bringing in their receipt, he adds.

At a time when most students are vacationing, travelling or working summer jobs, the bookstore's preparations for the September rush begin in earnest.

At the end of June, the bookstore staff conducts an email blitz of McGill departments, and later phones laggard professors to jumpstart the ordering process.

In July, the bookstore is inundated with requisitions, says Grant Zubis, the bookstore's textbook buyer.

While most orders are processed without delay, on occasion, Zubis says, he may suggest that the professor find another book.

"When a book is extraordinarily expensive, I will contact the professor and ask, 'Do you really want your students to buy that book?'" he says.

Provided a Canadian distributor or publisher has a book in stock, an order can take as little as one week to arrive.

Books coming from the U.S. are more likely to take two to three weeks, while those from overseas usually take a month or more. Books for some language courses come from as far away as Hong Kong, Zubis says.

Throughout July and August, McGovern, as floor coordinator, is occupied with the cumbersome task of setting up the basement.

As of mid-July, 100 book orders a week begin arriving and must be organized throughout the store. "Everything has to have a happy place to go," McGovern says.

By September, 85 percent of the books have arrived. The final 15 per cent is always late because either professors didn't know they were teaching a class until the last minute, or they changed their minds about a book or they simply forgot to put in an order, McGovern says.

"One of main culprits of why a book will be late is stock shortages when a number of universities are using the same books and if we don't get the order in first," he says.

The rush is over. When I return to the bookstore's basement two and a half weeks later, the scene is pacific. Two clerks are hunched over, bored, at the information desk. McGovern is at home sick, they say. It feels like the morning after a really great party.

A few days later, McGovern tells me the rush unfolded as smoothly as he could have hoped.

Though neither he nor General Manager Jack Hannon have figures, both suggest that sales were up this year. Hannon explains the increase as resulting from the double cohort and more orders from professors. The sales line, by the store's count, never lasted longer than 12 minutes, McGovern says.

"There's a whole host of problems that can happen and none of them did," says McGovern. "I'm basically the front line for problems and I didn't really have any customers complain about anything, which makes me happy."